Underwater Aliens

What has venom like a snake, a beak like a parrot, ink like a pen, the weight of a man, the length of a car yet can fit through an opening the size of an orange?

Octopus, not octopi (I recently learned that you can’t put a Latin ending, i, on a Greek work, octopus) look so alien and otherworldly that it can be hard to see them as anything more than an ‘other’ being but they are intelligent, fascinating creatures that often become many water enthusiasts favourite creature. As I often find when you learn a little about an animal they become infinitely more fascinating – the octopus is no different. I have always enjoyed watching them underwater – from how they change colour and shape to how they glide through the water, to how they move objects with their tentacles; they have always held a certain allure. We may find them difficult to relate to as they look so different to ourselves – realistically their body composition is body, head, legs – they are upside down – and eight legs too, with suckers on!

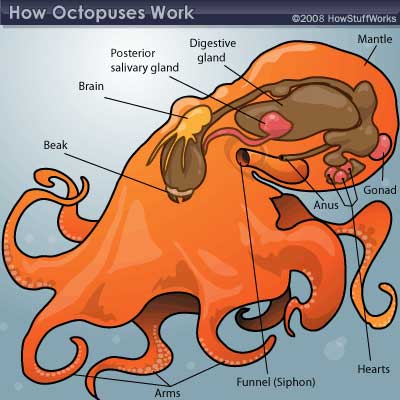

The octopus are in the mollusk family – this puts them in the same category as snails, slugs and clams, not something that we immediately think of as exciting or intelligent creatures. Yet the octopus is a cephalopod – part of the most advanced animals in the phylum, the word cephalopod means ‘head-footed’ and refers to the fact that their arms branch directly off its head. Whilst the other cephalopods (squid, cuttlefish) and molluscs sport some form of inner or outer shell, the octopus has none therefore it has had to become a little more cunning in its lifestyle. So it has its body or mantle at the top and this is a pretty muscular structure that houses the important internal organs such as gills, digestive system, reproductive system and hearts.

Yes hearts, plural. The octopus has 3 hearts. The reason behind this is because they don’t use hemoglobin to carry oxygen round their body. Hemoglobin is red because the binding protein contains iron. In an octopus the binding protein is hemocyanin, and it contains copper. This makes their blood blue. It is also a less efficient carrier of oxygen therefore to maintain a high blood pressure and thus more oxygen, 2 hearts are used to pump oxygen rich blood through the gills and the third circulates it around the body.

The octopus also has a well developed nervous system. The eye is very similar to our eyes except that they have the ability to see polarized light (like some birds and sunglasses) and they do not have a blind spot. The reason for this is because the optic nerve circles around the outside of the retina rather than connecting to a point on it. Each eye is able to move independently but they can only see up to a distance of about 8-10 ft. They also only have one visual pigment (we humans have three and are therefore able to see in colour) therefore an octopus is effectively colourblind! This makes their camouflage displays even more impressive. So how do they do it? One thought is that they can ‘see’ with their skin – 3/5 of an octopus neurons are in its arms not its brain therefore they contain a large level of autonomy and information. Just as we have voluntary and involuntary reactions (i.e. quickly removing our had from a hot surface is not something the brain needs to tell us to do because our peripheral nervous system has already done it) octopus arms are similar. They can function on their own accord – the brain delegates a job but the arm can decide how to do it! These arms contain hundreds of suckers. The suckers are in 2 rows and each one contains an inner and an outer chamber. The outer chamber is the broad suction cup that we see and the inner chamber is a small hole in the center that creates the suction force. These can also be exceedingly flexible and act independently. It also makes them very strong – it is believed that a 2.5inch sucker, such as can be found on a giant pacific octopus, is capable of lifting about 35lbs. Per sucker! And an octopus has hundreds of them!

Perhaps the most fascinating part of seeing an octopus in the wild is watching it change colour within a second it can go from white to purple, to brown, to pink or anything in between. Each individual has about 30-50 different camouflage patterns – they can change their colour, pattern and texture within about 7/10 of a second. They do this by having three different types of cells near the surface of their skin. The deepest layer contains the white leucophores and can passively reflect background light. This uses no muscles or nerves. The middle layer is composed of tiny iridophores. These reflect light (including polarised) and are used to make the greens, blues, golds and pinks. These cells are controlled by the nervous system and are associated with the neurotransmitter acetylchlorine (in humans this is also important in memory, learning and REM sleep), the more turned on this neurotransmitter is the more greens we see and the less turned on it is the more pinks and golds. The top layer is composed of chromatophores. These are tiny sacs of yellow, red, brown and black colour. Each one is contained in an ‘elastic’ container that can be opened or closed to reveal more or less colour. Camouflaging the eye alone, in the bar, bandit or starburst pattern can involve 5 million chromatophores. The octopus can change colour anywhere on its body except the suckers and linings of the mantle and funnel. It can also change its texture by raising and lowering fleshy parts called papillae to help it blend in with its environment.

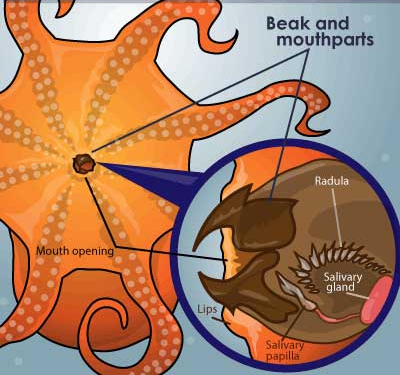

The octopus uses its excellent camouflage to escape predation but it also uses it to help it hunt. Some octopus hunt by stealth and others by speed but when they finally catch their prey they have an arsenal of weapons to help digest it. Food gets passed up the tentacle towards the beak, located on the underside in the center. This beak is similar to a parrots beak in that it is sharp and powerful. It is used to break open shells and also to tear flesh. It also has a radula, like a barbed tongue that can be used to help scrape an animal out of its shell once it has been opened. Finally it has a salivary papilla – a tooth covered organ used to drill into shells, this papila also secretes a saliva that erodes the shell and weakens the prey. Quite the array of digestive materials!

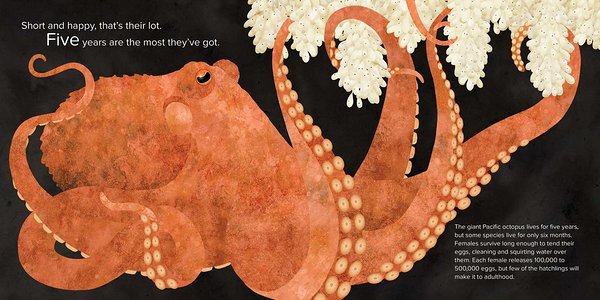

As with most animals their aim in life is to reproduce; but for octopus it comes with a high price – death. Most males die a few months after mating, if the female doesn’t eat them after the act that is, and females die soon after their eggs hatch. Males look different to females from the outside in that they have a hectocotylized arm – the suckers don’t go all the way to the tip but rather they get replaced with a ligula, a specialised organ for placing the spermatophore inside the female. Females can store the sperm from a few hours to a few months until they are ready to lay their eggs. When they do they lay upto 100,000 of them! These tend to be in strings that are woven together like strands of onion. They use a special glue to then stick them to the roof of their den. For months they will look after these eggs, not leaving them, not eating just caring for them until finally they hatch. When the young octopus hatch they are barely the size of grains of rice and they drift off into the ocean currents as plankton, where many do not survive but some gain in size before drifting to the bottom and starting their life. Whilst she cares for her young the female octopus condition starts to deteriorate and often she become paler and whiter as the muscles controlling the chromatophores start to loose tone and she dies soon after they are born.

So now that you know a little more about the octopus, hopefully you find them as fascinating as I do. Good luck searching for one on your next dive!

Photos are mine, other images courtesy of Google.